Save this article to read it later.

Find this story in your accountsSaved for Latersection.

Can a doodle also be a masterpiece?

It starts off as an elevation of the quotidian but transforms into something sadder and more reflective.

Much of what he talks about is a shoot he was assigned to do with the poet Allen Ginsberg.

As the two talk, they move around different parts of the apartment.

They make coffee, they drink tea and eat cookies.

They lounge in bed.

Distant sounds from the street drift in.

They touch each others legs and heads and feet, glancingly and sensuously, though not sexually.

Such sense memories arent there to precisely chart Peter Hujars path through Linda Rosenkrantzs apartment.

Her adoration of Hujar comes through, as well as her ease around him.

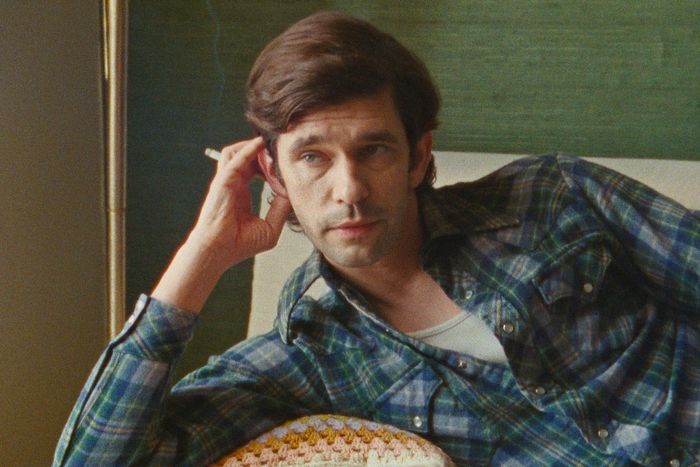

Whishaw gives Hujars words a matter-of-fact quality, but theres a slight hint of melancholy to him, too.

Hes filled with anxieties about his art and his work.

(The Ginsberg shoot, he says, is his first job for the New YorkTimes.)

Hell, hes filled with anxieties about going four blocks down to another part of the Village.

So loss is, in a way, built into the very concept of the film.

The intimacy draws us in, as if we might know these people.

At the same time, we also understand that well never know these people.

So, no, the film is maybe not a doodle.

Theres too much craft, too much care here for that.

But it is a masterpiece.