Save this article to read it later.

Find this story in your accountsSaved for Latersection.

Yet the prominence from such an award applies a pressure that many writers cannot withstand.

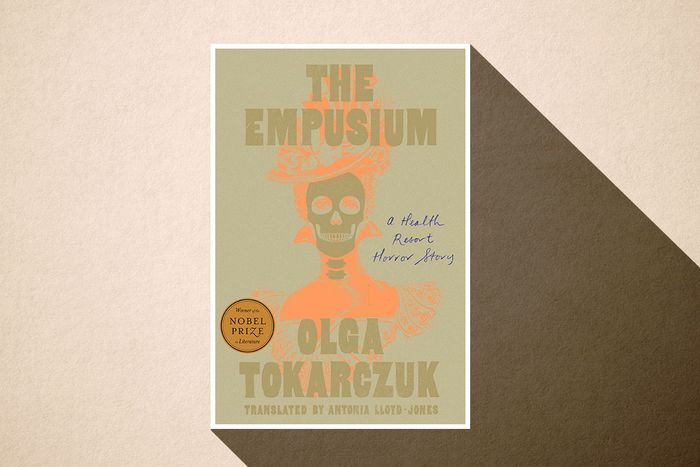

Such seems to be the case for Polish novelist Olga Tokarczuk, who won the Nobel Prize in 2018.

Unfortunately, her newest novel,The Empusium,only amplifies this pattern.

Merely breathing will stop the process of decay in your lungs, explains his doctor.

Every breath is curative.

Gobersdorf is a popular destination with patients from across Austro-Hungary and further afield.

So popular, in fact, that he cannot yet get a room at the sanatorium.

Yet there is something pointedly off about these dialogues.

The reader will have guessed this long before our humble protagonist.

Wojniczs sequences are narrated in a standard past-tense third-person, rarely straying from his thoughts and memories.

This is the voice of the Tuntschi, a mysterious forest-dwelling force that seems to exist outside time.

In changing her perspective, the old woman has liberated herself of body, sex, nationality.

Yentes vision knows no such borders, after all.

And in Gobersdorf, threats certainly loom.

And as Thilo discovers at the cemetery, one man from the village dies every November.

The residents of the guesthouse consume Schwamerei, a local liquor distilled from mushrooms with ostensibly hallucinogenic qualities.

Those hoping this will unlock the authors mystic side will be disappointed; its effect is much more convenient.

Many of the characters, including Lukas and August, have a lot to say about women.

They cannot raise children, or understand real art, or think deeply about anything at all.

They are feints, leading us back to a fundamental misogyny.

That last one is key.

Even before his Nobel win in 1929, Mann was the most prominent German novelist of his era.

So too is Tokarczuk in contemporary Poland.

Despite its historical setting, it is impossible to extractThe Empusiumfrom this context.

Tokarczuk seems desperately afraid that you not miss the point of her book or take away the wrong lesson.

She finds their misogyny odious, and so you must, too.

Rather than learning from the novel, it ends up instructing you.

So, too, the characterizations, which dictate exactly how we are meant to respond.

No one frightens her more than Wojnicz.

InIllness As Metaphor, Susan Sontag writes that tuberculosis was believed to purify those who suffered from it.

TB was the illness of innocents: The virtuous only become more so as they slide toward death.

The Polish student reads as a parody of this tendency.

Shy and naive, he has nothing to contribute to the arguments at the guesthouse.

These memories arise instructively, pre-interpreted, with no space for the reader to reflect or respond.

He exists for her as a purely symbolic creature, real only in what he signifies.

This unintentionally describes the novels treatment of Wojnicz.

His middleness becomes a muddle.

Tokarczuk cannot even risk having Wojnicz viewhimselfnegatively after all those years of observation and persecution.

Well, he was as he was, she writes during the big reveal.

He couldnt help it.

He thought of himself as normal.

A born victim, he remains eternally innocent.

An intersex person like Wojnicz is nothing more than an idea, a symbol to these people.

A work of literature is at bottom a mechanism for the generation of meaning.

The author brings the material and shapes it into a desired form.

This is how an artwork continues to live.

Irony, ambiguity, ambivalence: all create a chance for misunderstanding.

But they also create the necessary gap between author and reader that creates the space for meaning.

When it heeds the call of the Tuntschi,The Empusiumapproaches those earlier heights.

ButThe Empusiumis rarely more than it appears and frequently much less.