Save this article to read it later.

Find this story in your accountsSaved for Latersection.

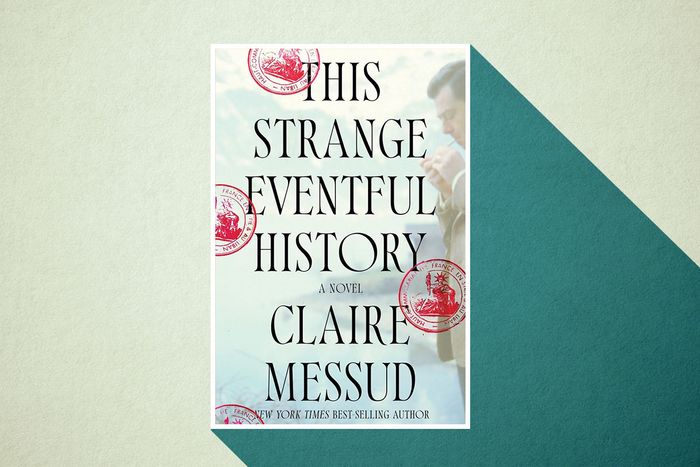

Claire Messuds best-known book,The Emperors Children, came out in 2006.

Messud was writing for a readership with a prelapsarian attention span.

Messud, who is 57, might point that out too.

On the subject of smartphones, shes an alarmist.

Its a terrible diminution.

Its afamily story with the weighty tone and generation-spanning structure that used to signify an Important Novel.

But does anyone want to read a good old-fashioned book these days?

Of course, the big family novel hasnt exactly gone away.

She seems aware of the downsides of her approach.

The big questions are here, about family and colonialismand grief.

But the real promise of a 425-page family epic is that it will provide an emotional punch, too.

On that, it delivers.

When the novel begins, the Germans are marching into Paris and the family has been separated.

Later, the dissolution of colonial rule in the early 60s forces them to leave Algeria for good.

But Messud is expansive in her descriptions of their insignificance.

These are not new subjects for the author.

But her new book is more literally biographical.

Messuds willingness to imagine the depths of her fathers self-disgust is both tender and shocking.

Messud isnt an explicitly political novelist.

The degrading effects of colonialism, though, are a preoccupation of hers.

History, she thinks, is largely experienced through the trappings of grief and fear.

Humans tend to be inadequate in the face of it, anxious and defensive.

I felt the readers version of museum fatigue.

As they trade chapters, the Cassars mull over their private grudges.

Barbara, Francois thinks, has a snarky Canadian superiority.

She, in turn, thinks her father-in-law Gastons habit of calling his wife a lay saint is repulsive.

Literary language is a kind of spell, she writes in the introduction of her 2020 essay collection.